www.ji-magazine.lviv.ua www.ji-magazine.lviv.ua

Taras Voznyak

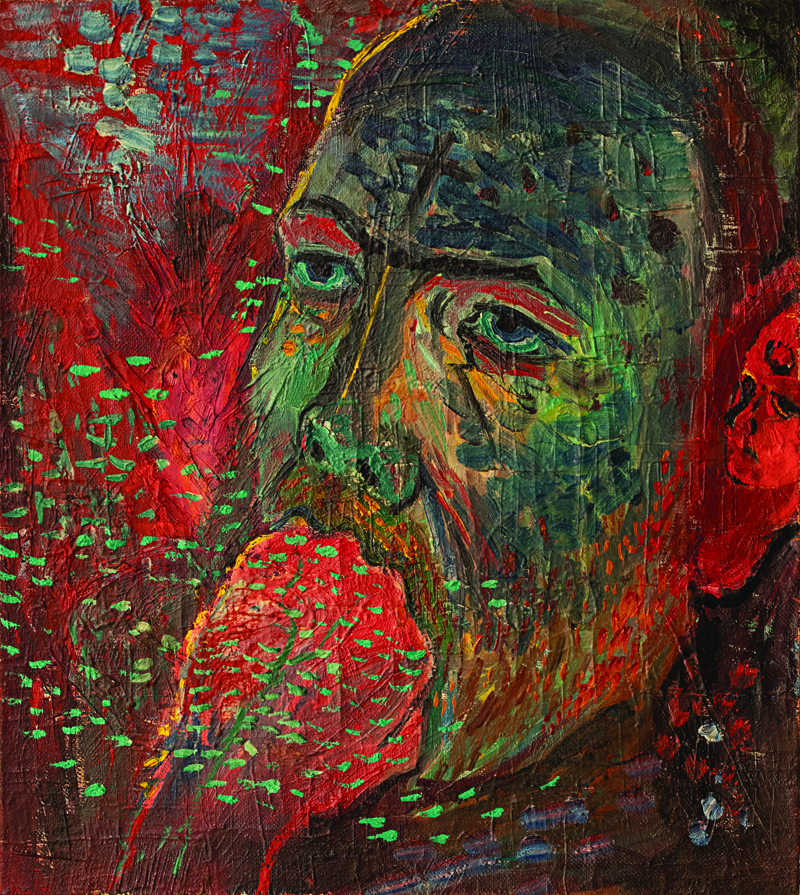

Myroslav Yagoda:

"Sunflowers Should Be Shown Together With His Ear"

La tristesse durera

toujours.

Sadness will last forever.

Vincent van Gogh’s last

words

When one starts on a journey, taking the first step is

the most difficult as it means tearing the veil of timelessness and

homelessness – time and space. Still, it seems to me that I have always known I

will have to take it. I have never been sure whether my first step will be worthy

of those spaces and territories which I must enter. Indeed, my mission is by no

means easy since it requires following the footsteps of Myroslav Yagoda

(1957-2018), a Lvivian explorer of the regions of great heresies, someone who

did not fit our cynical time. Of course, I cannot penetrate those regions quite

like him, really, for neither have I enough courage nor imagination – everyone

has his own way – but at least virtually, post factum. As an excuse, I may

refer to Immanuel Kant who would regularly take the same well-trodden, routine

route, but his walks between the university and his bachelor’s cottage

eventually made him reach the essence of things in themselves. After Myroslav

Yagoda had finished his earthly pilgrimage, it became obvious to all of us that

«in our civilized time, the time of progress and growth» he almost literally

repeated the existential trajectory of van Gogh. It was not by accident that one

of Yagoda’s programmatic paintings is called Van Gogh’s Sunflowers Must Be Shown Together With His Ear. Such was

the way of the artist, a genuine and sincere one. His ways were not as ordinary

as those of Kant – there were bouts of insanity, depression, and expressive

aggression; everything that may happen to someone who happens to be «other.» I

believe that Georges Rouault, another painter akin to Yagoda, took the same

route. He is less known than the great Vincent, even though he followed van

Gogh’s way as well. When Rouault died, Yagoda was born.

BIRTH

«Let me go and see Gregor, he is my unfortunate son!

Can't you understand I have to see him?», and Gregor would think to himself

that maybe it would be better if his mother came in, not every day of course,

but one day a week, perhaps […]

Franz

Kafka, «Metamorphosis»

Myroslav Yakovich Yagoda was born on August 23, 1957

in the village of Girnyk near Chervonograd, oblast

Lviv. His mother, whom he loved dearly, was Vira Petrivna.

In 1986

Yagoda graduated from Ivan Fedoriv Ukrainian Institute of Printing in Lviv.

Soon after that we met for the first time, in part thanks to Yurko Gudz’

(1956-2002), a writer from Zhytomyr and a literary rip – a rambler, half-poet

and half-philosopher, one of those eternal Ukrainian types that replicates the

famous archetype of Skovoroda. Yurko travelled a lot, following the philosophy

of combined lettrism, macoto, and hesychasm. In fact, it was when Zhytomyr

happened to bring into being – of course, thanks to Valeryi Shevchuk (b. 1939)

– perhaps the most intriguing literary school of those times, which emerged not

only around Schevchuk himself, and then perhaps the first independent and legally

distributed literary periodical, the Avzhezh,

published in Zhytomyr from March 1990 until November 1998.

As a

literary manager or agent, Yurko wanted to get in touch with a relatively

closed group of Lviv intellectuals, known as the «Lviv school», including Igor

Klekh (b. 1952), Grigoriy Komskiy (b. 1950), Yuri Sokolov (b. 1946), Kost’

Prysyazhniy (b. 1936-2015), Taras Voznyak (b. 1957), and Igor Podolchak (b.

1962).

At the

same time I was working on the first underground issue of the independent

cultural journal YI, published in

April 1989 after two years of continuous effort. It was Yurko, working with me

on the following issues, who suggested that we should include in our group an

artist from Lviv named Myroslav Yagoda. The idea was to design for YI an artistic layout, which was very

important to me and I was indeed looking for someone to take care of the next

number. The texts of such cult authors, whom I then highly appreciated, such as

Martin Heidegger, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Karl Jaspers, Paul Celan, Ingeborg

Bachmann, Erich Kästner, Hans-Magnus Enzensberger, and Witold Gombrowicz

required an appropriate design. Before that I was using the graphics of Anatoly

Stepanenko, another cult figure of the Lviv underground of the 1970s and 1980s.

At that

time, the office of YI was located in

a studio that officially belonged to the graphic artist from Lviv, Igor

Podolchak. In fact, however, it was ours, since Podolchak was using another

one. Gudz’ invited Yagoda to the studio at 18, Chekistiv St. It turned out that

the artist was a nice young man with a friendly smile and eyes of a dandy. I

remember that he was well dressed and very similar to Paul Verlaine, wearing

white linen pants, a dazzling white shirt, and a bright red pullover. When our

conversation was over, Gudz’, a wandering philosopher, stayed in the studio to

sleep there overnight, while Myroslav and I went home. Even though Yagoda

looked like a dandy, he did not fail to mention his schizophrenic condition,

which I took to be a fashionable prop. How could a young artist from Lviv be

just a banal prettyboy without a bit of some spice, such as a mental disease?

Alcoholism was much too common and had no particular appeal, AIDS was known only

as news to be found in newspapers. Tuberculosis was rare, or at least we, young

people, believed so. Schizophrenia seemed to us the most appropriate as

something vaguely intellectual. On the corner of Kopernika St. and Lenin

Boulevard (now Liberty), each of us took his own way, agreeing to meet on the

next day at Yagoda’s studio at 6 Marchenka St., now Tershakivciv St.

That was

how my frequent visits at Myroslav’s studio began, and his visits at my place,

too. Parties that I used to throw then were a sort of ritual for many people

who were contributing to that time, our time…

For me visiting

artists’ studios in attics, such as the studio of Podolchak, or in cellars, as

those of Klekh, Komskiy, or Evgen Ravskiy (b. 1966) was no big deal. In the

Soviet times it was absolutely normal, a kind of fringe benefit. Only those

artists who worked for the regime had their studios in regular apartments. Hordes

of rats, which considered studios to be their domain, did not shock me at all.

At my place it was like that, too – somehow, humans and animals managed to

share the same space in peace. It all comes back to me now: descending to the

basement, then a corridor and the door on the left. Myroslav opens it: the

smell of cigarettes and dense smoke. His studio consists of two rooms. Not long

before, it must have been a dwelling of an usher or a loader – in the Soviet

times, many Lviv families lived in such conditions. In one room there was a

sofa, a table, and a stack with books, no so characteristic of artists’ homes.

The studio proper was in the other one, and there Myroslav also slept.

Then the

first cup of coffee, the first glass of brandy. Myrolsav would rather

reluctantly show his graphic works to begin with. I am shocked, but keep

silent. Then we pass to the studio. Myroslav unfolds on the floor huge size

canvases. I am shocked again – the

canvases are truly epic, oversize – they definitely qualify to hang on museum

walls in more senses than one, and indeed they do not fit the «chamber,» somewhat

bourgeois Lviv style, particularly at the moment of a national revival, when

everything national is trivially associated with folklore in all its

manifestations. Yagoda’s idiom was radically different – as national as

anyone’s pain is, but also an idiom of someone who speaks with something that

does not belong to his world. With the Maker? The Devil? The Pain within

oneself, which cannot be born? Or perhaps with us? With me personally? From the

very beginning, when I saw his graphic works and paintings for the first time,

I realized that I came across something truly extraordinary.

PSYCHEDELICS

Gregor hardly slept at all, either night or day.

Franz Kafka, «Metamorphosis»

Myroslav’s

approach to his paintings was a little strange. He would simply take them off

the easel, since he had only one. With time, it became his personal style. Its

other aspects were: fungus that devoured those fantastic canvases, and cracks

all over since he treated them somehow ruthlessly, almost brutally, as if they

had been unwanted witnesses. The apotheosis of his «personal style» became

performances which included the last spectator of a given painting, falling off

the canvas when unfolded on the floor, «disintegrating under the spectator’s

very eyes.» (Vlodko Kaufman) Perhaps those paintings really were unwanted

witnesses of events that Myroslav would have rather concealed. Or he himself

was their last spectator? If so, maybe the paintings made during an act of

creation which was not just the process of painting itself but a performance,

were only byproducts, a residue of his creative self-realization. As the time

passes, I am more and more inclined to see Yagoda as a happener, and not just

because he was arranging his own life. The happening of his artistic life was

forty years long – a series of isolated happenings with paintings as their

results, which is particularly true in respect to the 1980s. He did not work on

them meticulously, for years, but produced them in bouts of creative frenzy

mixed with joy or pain. To realize that, it is enough to take a look at the

sweeping brushstrokes on canvas. Quite often it is a moment caught in paint,

like in Zen poetry. Just like there, what is the most important is not the

scroll with a quickly recorded poem, but the moment of creation which the monk

can hardly fix on the scroll with his ink. I believe that in the short moments

of creation Yagoda would not have been able to work in any other way.

This is

why I still have a question to which Myroslav will never give an answer and we

are bound to get lost in its different versions: was it that the result of his

acts of creation was a finished picture? Or maybe it was that very moment when

he was actually painting, conditioned by the concealedness of that Someone who

could give answers to his own, not just tantalizing but genuinely hellish

questions. Yagoda had many more of them than an ordinary human being. His lot

was truly hard. In my view, the essence of his art consisted in the very act of

asking, begging for an answer, harassing not us, mortals, but Someone else.

Indeed, mortals remained far beyond the limit of his primary interest.

Sometimes he would paint «portraits,» being generous, trying to give thanks,

which makes them so valuable as Myroslav’s reactions from the depth of his

soul.

Still,

his art penetrated quite different spaces – the spaces of Great Heresies. With

a superhuman effort he attempted to obtain, elicit Ultimate Answers to Horrible

Questions, to the questions which for an ordinary Philistine are impossible not

only to ask, but even to think of. These questions are horrible because a living

human being may realize that answers to them are similar to those which Saint

John of Patmos received in his Apocalypse: «After this I looked and, behold, a

door was opened in heaven; and the first voice which I heard was as it were of

a trumpet talking with me; which said, Come up hither, and I will show thee

things which must be hereafter.»

Keeping

all that in mind, one may ask another strange question: did Yagoda himself take

part in those nocturnal happenings which resulted in his paintings and

graphics? It is obvious that he must have been struggling with something. Was

it his mental condition? His split personality? We must not forget that this is

what schizophrenia is like: personality split into two, three… Was one of those

others the One who could give Ultimate Answers to Horrible Questions? Which

Yagoda elicited the Answers from Him? Was it the one who still stuck to the

straws of rationality, or the one who was watching him from a distance,

gnashing his teeth?

Then

Yagoda would take the canvas from the easel, fold it into a roll, and throw it

on the shelf. A mass of unfolded canvas grew for years or decades; colors were

bleeding, rotting, falling off. Was he saving those exorcisms for himself or

did he want to hide in those rolls something that should not have come to

daylight, to sweep away, half-consciously, the traces of his shame? Who knows?

Maybe, coming back to his senses, he was pretending to be mad to make others

leave him alone, not to say too much?

TERRIBILIS

MYROSLAV YAHODA

[…] then, right beside him, lightly tossed, something

flew down and rolled in front of him. It was an apple; then another one

immediately flew at him; Gregor froze in shock; there was no longer any point

in running as his father had decided to bombard him. He had filled his pockets

with fruit from the bowl on the sideboard and now, without even taking the time

for careful aim, threw one apple after another. These little, red apples rolled

about on the floor, knocking into each other as if they had electric motors. An

apple thrown without much force glanced against Gregor's back and slid off

without doing any harm. Another one however, immediately following it, hit

squarely and lodged in his back; Gregor wanted to drag himself away, as if he

could remove the surprising, the incredible pain by changing his position; but

he felt as if nailed to the spot and spread himself out, all his senses in

confusion.

Franz

Kafka, «Metamorphosis»

But

fortunately youth can live through or just ignore such serious things. It is light-minded

and perhaps because of that there is still life on earth, since if all of us

took to heart those Horrible Questions and began to bear witness to the

Ultimate Answers… I was still light-minded enough to return, having left

Yagoda’s studio, to vanity and vexation of spirit (Eccl. 1:14, 2:11).

Myroslav

himself did not live in permanent creative trance either – his tormented soul

was also attracted by profane life. He plunged in love affairs, inebriety, and

artistic plans related to various projects. Fortunately, with time those

artistic circles of Lviv which could see the difference between genuine art and

decoration acknowledged Yagoda’s «otherness» and in spite of some natural

apprehension – they had good reasons to feel uneasy about the painter and his

works – developed respect for that more and more terrifying and unusual man.

Yagoda’s fame of a «horrifying» and «great» artist grew not so much in Lviv,

but abroad – Myroslav had his own Ukraine, he did not seek recognition in Kyiv

or Kharkiv. His infernal Lviv studio became a very peculiar place – it could be

visited only by first rate intellectuals or connoisseurs. Simpletons were not

expected to come – at any rate, they were either shocked by what they saw or

understood nothing. A final visit at Yagoda’s place was the climax of

experience for every intellectual who was courageous enough to take in Lviv the

risk of a metaphysical adventure.

In the

1990s Myroslav reached his creative peak. It was the heroic period of the expressive,

crazy, monumental Yagoda – Yagoda the prophet, Yagoda-Ecclesiastes,

Yagoda-Isaiah. Such serious comparisons may seem exaggerated and they are –

from the point of view of historical humanity. But what is important in art, is

one’s inner history, inner struggle with oneself and others. We, spectators,

watching that struggle from without, can only guess what is going on within the

artist. My presumptions concerning Yagoda’s inner conflicts, only from time to

time represented on canvas or articulated in his poems, allow me to make such

far-reaching comparisons. Myroslav was struggling like Saul who became Paul,

but with one essential difference: the biblical Saul struggled with the Angel

only once and became Paul forever, while the Lviv artist was returning to the

condition of Saul again and again to face himself, his schizophrenia, and his

eternal Opponent who did not lift the veil from his face. Or perhaps He did it

at the very last moment of Myroslav’s life?

Yagoda’s

1990s were illuminated by visions, dreams, and nightmares – great metaphysical

paintings. No less monumental were his graphic works from that period – their

smaller size does not make any difference. The combinations of black and silver

can hardly conceal the yawning abyss of Myroslav’s soul. He did not know what

to do with himself, how to disentangle himself from the ties of his body, his

illness, his suffering which waxed outside his studio and time and again filled

it up to the ceiling. Outside were also the difficult 1990s…

Was

Yagoda an autodidact? Not at all, and not because he graduated from the

Institute of Printing. Like everyone else, he learned his art from Goya, van

Gogh, Rouault, and Oskar Kokoschka, as well as, most certainly, from Francis

Bacon. Bacon’s painting, just as Yagoda’s, is a testimony of the tragedy of

existence. It is a kind of outcry that respects no limitations or boundaries.

The subject matter is neither animals nor humans, but lonely, stretched figures

tortured at some secret, intimate places. Those figures are mostly dis-figured

monsters; one-eyed, handless, with amputated limbs. Did Yagoda see Bacon’s

original works? Certainly not. Still, he saw them perfectly well with his

mind’s eye. Interestingly, both for Yagoda and Bacon one of the fundamental

motifs was that of stretching. They themselves were stretched. Van Gogh,

Rouault, and Bacon ask the same horrible question with the words of the

Stretched One: «What am I guilty of?» Then, totally exhausted with their

creative inquiring, they fall in despair: «My God, My God, why hast thou

forsaken me?» (Mark, 15:34)

METAMORPHOSIS

The first thing he wanted to do was get the lower part

of his body out of the bed, but he had never seen this lower part, and could

not imagine what it looked like; it turned out to be too hard to move; it went

so slowly; and finally, almost in a frenzy, when he carelessly shoved himself

forwards with all the force he could gather, he chose the wrong direction, hit

hard against the lower bedpost, and learned from the burning pain he felt that

the lower part of his body might well, at present, be the most sensitive. So

then he tried to get the top part of his body out of the bed first, carefully

turning his head to the side. This he managed quite easily, and despite its

breadth and its weight, the bulk of his body eventually followed slowly in the

direction of the head. But when he had at last got his head out of the bed and

into the fresh air it occurred to him that if he let himself fall it would be a

miracle if his head were not injured, so he became afraid to carry on pushing

himself forward the same way. And he could not knock himself out now at any

price; better to stay in bed than lose consciousness.

Franz

Kafka, «Metamorphosis»

The

1990s were the time when in Lviv a new, no longer Soviet artistic milieu came

into being, including such artists and authors as Volodymyr Boguslavskiy (b.

1954) , Andriy Sagaydakyvskiy (b. 1957), Vlodko Kaufman, Yurko Kokh (b. 1958),

Viktor Neborak (b. 1961), Nazar Gonchar (1964-2009), Ivan Luchuk (b. 1965), Petro

and Andriy Gumenyuk (b. 1960), Mykhailo Moskal (b. 1959), Evgen Rabskiy, and

Vlodko Kostyrko (b. 1967). Also the first independent cultural institutions

were founded, with such significant phenomena as «Vyvych» (1990), a youth

festival of alternative culture and non-traditional genres of art, which was a

boost for the emergence of «Dzyga» Union of Artist (1993), followed by the

first newspaper Postup (1997), Publishers’

Forum in Lviv (1994), the second largest Ukrainian annual book fair, and a

festival of contemporary music «Kontrasty» (1995). Before that, still in the

Soviet Union, there appeared literary groups «LuGoSad» (1984) and «BuBaBu» (1985)

as well as the journal YI (1989). The

first art managers – Yuri Sokolov, Antonina Denysyuk, and Georgiy Kosovan – had

a lot to do.

All that

happened thanks to the youthful energy and early maturity of that diamond-stuck

sky over Lviv, a new city with a new myth, not that of suffering, but of

creative potential. That new Lviv came into being under our eyes and thanks to

our effort.

All

that, of course, happened with an artistic flair, a proper entourage, and

bravado – full of cigarette and weed smoke, in a company of fascinated

nymphets. That joyful stream did not miss the studio of the Master of Dusk –

Yagoda, smiling sardonically, leniently allowed the lively flotsam and jetsam

flow across his den. It was just another face of Myroslav-the Satyr, a goat-legged

worshipper of one more ancient god, Dionysus, Christ’s predecessor. The very

name of Dionysus means «son of god» (dio-nysos),

which seems to be an allusion to the Son of God. Dionysus is close to

Yagoda-the Satyr not because he is the god of wine, but because he was the

first god that suffered, a god who experienced suffering. Taking part in the choruses

celebrating the feast of Dionysus, satyrs gave way to the rise of Greek tragedy

and satirical drama. The earthly torments – «Dionysian woes,» his death and

revival – were the gist of the orphic mysteries. For Greeks, Dionysus was,

strangely enough, not only an incarnation of beauty and strength, but also of

ecstasy, inspiration, and suffering. A combination of inner suffering and

sardonic grimace with time became Yagoda’s mask which gradually transformed a

brilliant dandy into the satyr of the Lvivian infernal rituals. It was not only

alcohol that caused the transformation of Gregor Samsa, or Kafka himself, into

a monstrous insect: «One morning, when Gregor Samsa woke from troubled dreams,

he found himself transformed in his bed into a horrible vermin. He lay on his armor-like

back, and if he lifted his head a little he could see his brown belly, slightly

domed and divided by arches into stiff sections. The bedding was hardly able to

cover it and seemed ready to slide off any moment. His many legs, pitifully

thin compared with the size of the rest of him, waved about helplessly as he

looked.» This is actually about Myroslav…

As it

happens, Myroslav Yagoda had two faces – one which was his own and the other

one, a larva behind which he was hidden. Or perhaps he was hiding there from

himself?

TIME

AND VOICE

«This is something that can’t be done in bed,» Gregor

said to himself, «so don’t keep trying to do it.»

Franz

Kafka, «Metamorphosis»

One must

not forget that the last twenty-seven years in Ukraine have been the years of

an ongoing revolution which time and again explodes and then subsides. In spite

of all his cosmopolitism, Myroslav had no doubt about his national identity: «This

is my land, I am Ukrainian and will always be.» He said that not because he

liked wearing on holidays an embroidered shirt – his Ukrainian program was best

articulated through his working with the Ukrainian word. Also in poetry Yagoda

developed his own, unique idiom. His Ukrainian speech was by no means sweet, as

it sometimes happens in our country, or lachrymose. He did not use the language

but created it – he struggled with verbal clumsiness, learned how to speak. In

fact, he was learning like deaf and dumb people – to be able to speak with his

great Interlocutor whose speech is far from that of sweet-voiced versifiers who

believe that their chants are a dialogue with Him. Unlike them, Yagoda in his

poetry struggled through the thorny thicket of speechlessness, howling like an

animal to the Great Silence. Was that dilettantism as well? Not at all. I have

already mentioned his collection of books, which at that time was quite

impressive, often supplied by those who had the honor to visit him in his

studio. I have one of the best private libraries in Lviv, but at times I would

borrow one of Myroslav’s books.

Myroslav

Yagoda was a painter of the late 1980s. His artistic career continued, but in

my opinion it reached its climax during that rather dark yet also hopeful

decade. At that time the shell of the Soviet system started ultimately falling

apart, falling off in pieces like an old layer of paint. Censorship was no

longer as strict as before and the nonconformist art could come to light.

Definitely, its quality and orientation varied. Until then it had to exist

clandestinely under the surface of the socialist realism in private studios and

apartments – it was impossible to find out what the genuine artistic life in

general looked like. Sometimes one could take a look at real masterpieces, on

other occasions at sheer dilettantism which believed in its alleged uniqueness.

In the era of late Soviet Union there was a lot of epigonism, and no wonder since

Ukraine did not take part in the global art system that had its particular

logic and history. To be honest, we could only reconstruct its basic blueprint,

having more or less accidental access to its fragments. Quite often, those were

just illustrated art books of rather poor quality, or even art journals that

occasionally made their way to the other side of the iron curtain – Polish or

Hungarian replicas of whatever was going on in the West. Art critics and

artists did their best to grasp new developments ex post, working almost like paleontologists. They were

reconstructing tendencies that were more or less historical, trying to work on

the basis of what they could find. That is why there were in Ukraine so many

second or third hand impressionists, surrealists, and cubists. Certainly, that

was enough to decorate the apartments of the half-nonconformist intelligentsia

– actually, that is enough even today. Still, Myroslav Yagoda, although in the

beginning he was no grand seigneur of

the Lviv art world, did not take that option. He decided to play for much

higher stakes. I think that at that time no one realized it, even though many

artists were as sincere as Myroslav. However, sooner or later, after they got

married and children appeared, they had to support the family and forget about

their ambitions in favor of marketable parlor art that pretended to be genuine.

There would have been nothing wrong with it, if not for its aggressive

ubiquity, while Yagoda took a different route – into the wilderness. I do not

remember a single moment when he would have doubts as regards his resolutions.

One might say that it was caused by his psychological constitution or even

deviation, for he was always unusually adamant, saying, «You don’t understand

anything, it’s great!»

One of

the symptoms of the artistic revival in Lviv in the 1980s was a series of artistic

events, including exhibitions. Those «cryptoshows» were still organized in

conspiracy since KGB was on alert, though not as omnipotent as before. In the

1980s such attic exhibitions were organized clandestinely by Sokolov. The first

legal show of the Lviv nonconformist art, with 111 participants, was «Invitation

to Discussion» [Zaporoshenya do dyskusiy] in 1987, which took place in the

church of Our Lady of the Snows, then Museum of Photography. In 1988, Sokolov

organized another exhibition, called «Theater of Things» [Teatr rechey]. It was

one of the first examples of «environment» in Ukraine.

However,

also at that time Myroslav Yagoda did not show up in daylight but stayed in the

underground. He joined neither the glamorous salon, nor the tamed «non-conformists,»

plunging in bottomless paroxysms and sheer nakedness of suffering identity. His

art seemed to reveal his madness – dense, wide brushstrokes, brutality, and

extreme openness of expression, no limitations or inhibitions. In the purist

and patriotic Lviv of those times there were few who could comprehend that. Few

were ready to understand such testimony of the moment – the dominant social

temper was hope, which was good – when Yagoda with all the painful sincerity of

his art pointed at the profound abyss of suffering and despair, which indeed

haunt every human life.

When the

Soviet Union collapsed and Ukraine became independent, it experienced an enormous

explosion of art which became the hotbed of a new artistic canon. Particularly

powerful was that explosion in Kyiv, where a new cultural environment came into

being, even though the local artists would possibly protest against such

generalization since they believe that each of them was truly unique. Still,

Yagoda did not join in and stood separately, resisting any attempts at «advertising.»

He preferred to keep fathoming the bottomless Horror, instead of enjoying the

pleasures of PR.

In fact,

during those years Myroslav was coming of age as a mature painter. Strangely

enough, he combined some almost patriarchal Ukrainian elements with

unbelievable cosmic consciousness, a strong national identity with

all-encompassing cosmopolitism. He was received with the same respect in Lviv

and in Vancouver, which perhaps explains why his art was soon highly

appreciated abroad. Foreigners could fairly easily find in it a way into the

complexity of both human and specifically Ukrainian situation. His studio was

visited by numberless distinguished guests from different countries, including

a renowned German songwriter, social activist, director, and journalist Walter

Mossmann, as well as many outstanding Ukrainians.

Yagoda

was becoming more and more famous – his poems were translated into Polish, his

plays into German. At the beginning of the 21st century, the Maryia

Zan’kovetska National Academic Theater staged his drama «Nothing» [Nishcho]. It

was staged once more by the «Nebo» theater in 2002, and then, in Hungarian, in

the Regional Hungarian Theater in Beregovo, a Ukrainian city with a sizable

Hungarian minority population, directed by the well-known director Attila

Vidnyanszky. Actually, Yagoda’s collaboration with Vidnyanszky continued:

later, he designed stage decorations for a play based on the life of

Shakespeare. Both artists also prepared in Beregovo a successful performance of

Adam Mickiewicz’s Forefathers’ Eve,

and in the National Theater in Budapest they worked together on Shakespeare’s «Winter’s

Tale.» At the turn of the century, exhibitions in Poland, Hungary, and Austria

followed: in 1998, in Graz, as part of the project called «Cultural City

Network»; in 2006-2007, a painting exhibition and a performance «Fisherman» [Rybalka]

in Warsaw; on August 23, 2007, presentation of a book of poems Dystancyia Nul’ in Lviv; on February 23,

2008, presentation of a catalog of 24hours.ua,

and then a report from Yagoda’s Warsaw one-man show from 2007 in Lviv again. On

his own, Yagoda published three books of poems: Chereposlov (2002), Dystancyia

Nul’ (2006), and Syaymo (2008). His

last book was Paralelni svity (2011),

published by Gamazyn Press.

In

February-March 2001, the city of Graz invited Myroslav Yagoda to benefit there from

its grant program «Cultural City Network.»

MEDICAL

HISTORY

Hardly had that happened than,

for the first time that day, he began to feel alright with his body; the little

legs had the solid ground under them; to his pleasure, they did exactly as he

told them; they were even making the effort to carry him where he wanted to go;

and he was soon believing that all his sorrows would soon be finally at an end.

He held back the urge to move but swayed from side to side as he crouched there

on the floor. His mother was not far away in front of him and seemed, at first,

quite engrossed in herself, but then she suddenly jumped up with her arms

outstretched and her fingers spread shouting: «Help, for pity's sake, Help!» The

way she held her head suggested she wanted to see Gregor better, but the

unthinking way she was hurrying backwards showed that she did not; she had

forgotten that the table was behind her with all the breakfast things on it;

when she reached the table she sat quickly down on it without knowing what she

was doing; without even seeming to notice that the coffee pot had been knocked

over and a gush of coffee was pouring down onto the carpet.

«Mother, mother», said Gregor

gently, looking up at her.

Franz Kafka, «Metamorphosis»

As I

have already mentioned, when we met for the first time, Myroslav told me that

he was a schizophrenic. At that time I had doubts whether it was just an

artist’s pose, taken to become «interesting» to the others, or he really

suffered from a serious mental disease. At first, I thought the former was

true, but with time I had to change my mind, particularly being a witness to

his continual crises. He tried to cure himself with some pills but alcohol

abuse did not support that kind of therapy. Often his alcoholic excesses turned

into artistic ecstasy since heavy drinking coincided with the peaks of creative

energy. Still, that could not go on for long and sometimes Yagoda would ask me

for help. To help him, I requested Professor Oles’ Filc, an outstanding

psychiatrist, at that time director of the Kulparkiv Psychiatric Hospital in

Lviv, not only to admit the painter to hospital, but to treat him there a

little unlike other patients. And Professor Filc did help, even though Yagoda

was unfortunately unable to escape from himself. The only thing that could be

done was to get him out of another crisis.

In

the end, Myroslav’s most serious problem was no longer his mental disease, but

his alcoholism and physical disability which resulted from his unusual and

self-destructive lifestyle. While during the first stage of his artistic

development, drinking combined with schizophrenia somehow boosted long periods

of great activity, later alcohol prevented them. Finally, during the last few

years, he could not paint at all, though still sometimes wrote poetry.

MINOTAUR

It was not until it was getting dark that evening that

Gregor awoke from his deep and coma-like sleep. He would have woken soon

afterwards anyway even if he hadn't been disturbed, as he had had enough sleep

and felt fully rested. But he had the impression that some hurried steps and

the sound of the door leading into the front room being carefully shut had

woken him. The light from the electric street lamps shone palely here and there

onto the ceiling and tops of the furniture, but down below, where Gregor was,

it was dark. He pushed himself over to the door, feeling his way clumsily with

his antennae - of which he was now beginning to learn the value - in order to

see what had been happening there. The whole of his left side seemed like one,

painfully stretched scar, and he limped badly on his two rows of legs. One of

the legs had been badly injured in the events of that morning - it was nearly a

miracle that only one of them had been - and dragged along lifelessly.

Franz

Kafka, «Metamorphosis»

Regardless

of his fame, Yagoda did not change his lifestyle. On the contrary, in the

labyrinth of his studio he became a kind of Minotaur, a terrible half-bull,

half-human being with a human body and a bull’s head. During his last years,

his neck resembled that of a bull as well; he could not move it, so he would

turn around with the whole body. With time, the poor living conditions in the

Lviv basement, chronic colds, and general neglect of health had more and more

impact. His thick brows and blood crust on his nose and jaws also contributed

to his Minotaur-like appearance. He liked scaring people – sometimes playfully,

sometimes more seriously. Only his good eyes showed that he was not doing it in

earnest.

His

studio was changing as well, depending on his mood, the alcohol level in his

blood, mental condition, and, last but not least, cash balance. There were

periods when he was completely lonely. I remember that sometimes it was hard to

get inside because of rats that had to be removed by force. Perhaps they became

Myroslav’s domestic animals – he may have been joking, or indeed telling the

truth that particularly in winter they were seeking warmth on his chest. We

must decide by ourselves if it is true. Only recently someone has made a remark

that during his last years Yagoda limited his world to about five hundred

meters from the studio. With time, the circle grew smaller and smaller and

eventually transformed into a black hole of non-being.

His last

days. The end of winter of 2018 was severely cold. Early in February I got a

phone call from a friend who was also taking care of Myroslav that the heating

system in the studio broke down and only a brick on the gas stove raised the

temperature inside just a bit. I was scared that he would freeze to death and

called technicians who did their best to fix the heating which unfortunately

kept collapsing. Someone brought an oil heater but the fuses did not hold. They

found Myroslav Yagoda dead near the stool…

STAGES

OF MYROSLAV YAHODA`S ARTISTIC EVOLUTION

The first thing he wanted to

do was to get up in peace without being disturbed, to get dressed, and most of

all to have his breakfast. Only then would he consider what to do next, as he

was well aware that he would not bring his thoughts to any sensible conclusions

by lying in bed. He remembered that he had often felt a slight pain in bed,

perhaps caused by lying awkwardly, but that had always turned out to be pure

imagination and he wondered how his imaginings would slowly resolve themselves

today. He did not have the slightest doubt that the change in his voice was

nothing more than the first sign of a serious cold, which was an occupational

hazard for travelling salesmen. It was a simple matter to throw off the covers;

he only had to blow himself up a little and they fell off by themselves. But it

became difficult after that, especially as he was so exceptionally broad. He

would have used his arms and his hands to push himself up; but instead of them

he only had all those little legs continuously moving in different directions,

and which he was moreover unable to control.

Franz Kafka, «Metamorphosis»

The

early period of Myroslav Yagoda’s artistic development I would call «psychedelic.»

Then the most important for him was the act of creation as such, while a

painting or a graphic work – the results – were of secondary importance.

Sometimes, he was so deeply immersed in his psychedelic void that we could get

from there very few hardly comprehensible pictures. On other occasions, it was

the reverse – the pictures were so clear and harrowing that it was scary to

look at them. Still, the common denominator of Yagoda’s attempts to delve into

those bottomless spaces was his readiness to become one with the creative act.

From such trips into the abyss one could just as well never return and get lost

either in the disease, or in alcohol, or in both. At least it was extremely

difficult to regain one’s senses and indeed many failed to do it.

With

time, however, Yagoda got used to his mental condition, which at the turn of

the century resulted in a change of his artistic idiom. In my opinion, he

gradually abandoned his former, extremely expressive manner of painting in

favor of a more controlled, intellectual, and even aphoristic and purist one.

Perhaps the change was triggered by psychological self-defense – he made an

effort to save himself from destruction. Still, the experience of the former

ecstasy left its mark. Also, he was still driven by the need to let his

tensions out, to get rid of them, and to share them with us in any form – that

of painting or poetry. Thinking about his pictures and then painting them,

Yagoda would begin not with emotions, but with some sort of intellectual

construction that contributed to a whole semiotic universe, a code that he used

not so much as a mode of description, but a manner of world perception. All the

signs of that code – apples, skulls, fingers, phalluses, crosses, earthworms,

adders, sheep, moons, suns, stars, comets – call for interpretation. At the

beginning of the 21st century, the painter began to drift from

immediate expression toward personified conceptualism. His works were becoming

more ascetic, less painterly in the literal sense of this term – someone might

say that they were even too cerebral. That period of his artistic evolution may

be called «semiotic» since Yagoda was trying to convey his former and current

experience of probing the ineffable with of signs, clues, and references. He

did not «cipher» his messages to the world in the form of signs and images, but

«deciphered» that which could only be shown with signs. For him, signs were not

representations of something that could not be represented, but only

indicators, signposts pointing at proper directions. During that period, his

paintings turned into maps that conventionally reproduced his intimate spaces,

or guideposts showing the way to those areas beyond our reach.

A shift

from painting to literature was a logical conclusion of that stage. Significantly,

Yagoda’s poetry is not rooted in meaning, but in specific signs, too. Still,

speech – living speech – is always a field of meanings. The poet plays with

signs, makes them collide and influence one another. In other words, he

violates the logic of speech, capriciously subverts its conventional

underpinning. His Ukrainian idiom is very far from the standard of

communication. In fact, as every outstanding poet, Yagoda creates his own,

idiosyncratic diction that can be called Ukrainian with some reservations.

Sometimes his utterances cannot be understood as they are not utterances, but

hardly articulate messages of an oracle, a Pythia.

That was the final period

which I would call «semantic.»

CONCLUSIO

«What now, then?», Gregor asked himself as he looked

round in the darkness. He soon made the discovery that he could no longer move

at all. This was no surprise to him, it seemed rather that being able to

actually move around on those spindly little legs until then was unnatural. He

also felt relatively comfortable. It is true that his entire body was aching,

but the pain seemed to be slowly getting weaker and weaker and would finally

disappear altogether. He could already hardly feel the decayed apple in his

back or the inflamed area around it, which was entirely covered in white dust.

He thought back of his family with emotion and love. If it was possible, he

felt that he must go away even more strongly than his sister. He remained in

this state of empty and peaceful rumination until he heard the clock tower

strike three in the morning. He watched as it slowly began to get light

everywhere outside the window too. Then, without his willing it, his head sank

down completely, and his last breath flowed weakly from his nostrils.

Franz

Kafka, «Metamorphosis»

This is

how I see Myroslav Yagoda, artist and poet, after many years of knowing him. Certainly,

this is just the first attempt to remember him from a very short distance, but

it is important nonetheless. I have tried to pin down the times when he lived

and when we still live now.

Knowing

Yagoda for a longer period of time and getting used to his «theater for the

profane,» one would eventually realize that behind it lived a human being that

made for himself a hiding place behind a mask of the enfant terrible, bum,

Minotaur, and drunk – that behind his apparent bravado or even aggression, his

werewolfish last years, there was a delicate, sensitive, and good man.

The

present text is only my personal recollection of Myroslav Yagoda. If someone

remembers more about him, or remembers something else, he will write his own testimony.

Or not. At any rate, there is no exaggeration in a statement that Yagoda’s art

is absolutely unique, akin to nothing, and very sincere, both in respect to

himself, and to others. Therefore it still waits for a profound and

comprehensive analysis that will place it in our Ukrainian and global artistic

canon.

Translated

by Marek Wilczynski

|